Special Edition Spring 2022: Humanities Keep Us Human

How one St. Kate’s alum is speaking out to preserve humanities programs at colleges across the country

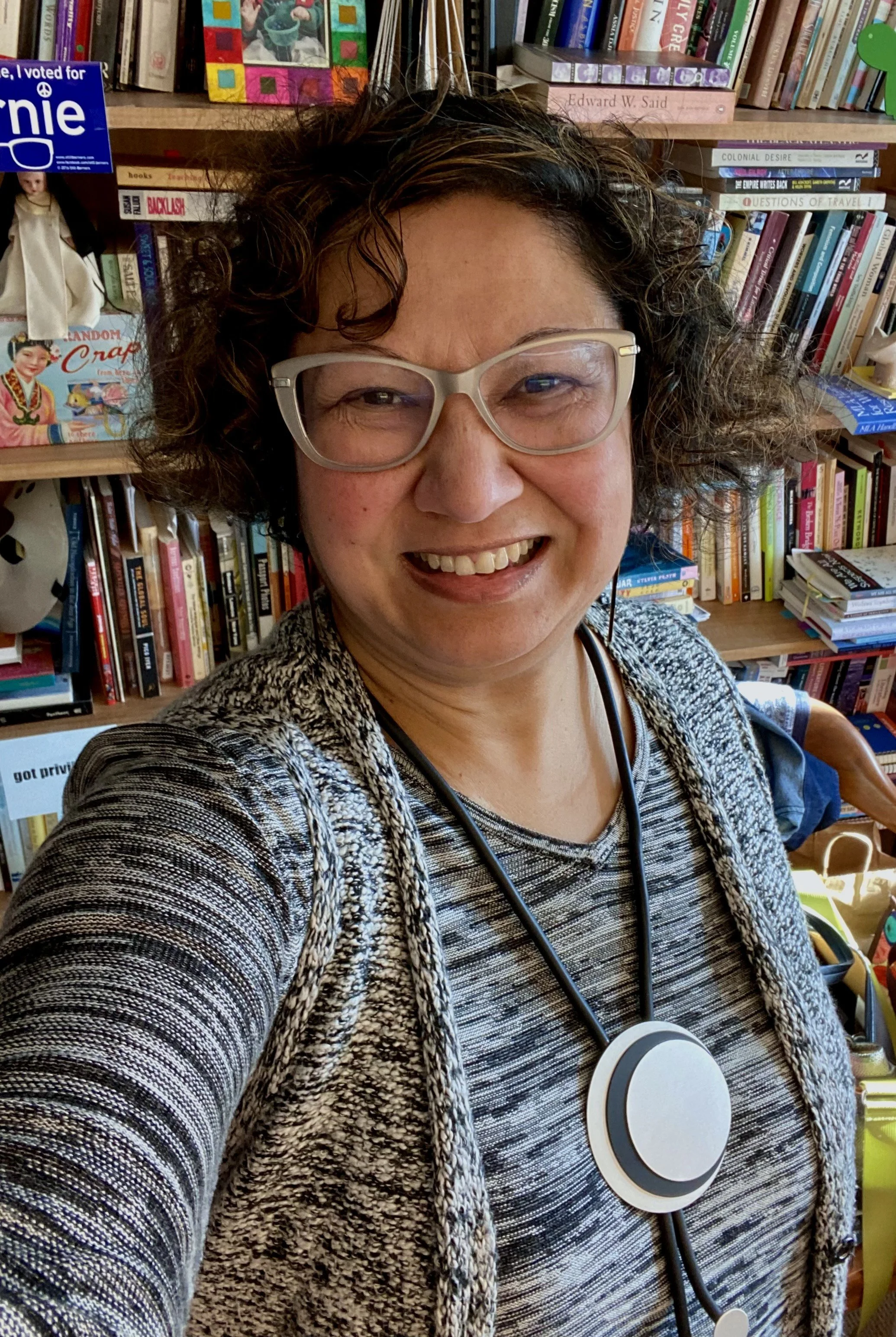

Reshmi Dutt-Ballerstadt is a St. Catherine University alumna, studying English and sociology during her time here. Now, she is the Edith Green Distinguished English professor at Linfield University and the editor of Inside Higher Ed’s column Conditionally Accepted. She told me that her own liberal arts education at St. Kate’s has helped shape her into the liberal arts professor she is today. In addition to these accomplishments, Dutt-Ballerstadt has recently been involved in a freedom-of-speech conflict born from frustration surrounding the devaluation of the humanities fields.

Dr. Anne Maloney has been a St. Kate’s professor of philosophy for thirty-five years and is one of the many supporters of Dutt-Ballerstadt’s opinions. I had the privilege of interviewing both of these women to find out about this hot-button issue called “academic prioritization.”

In her 2019 article “Academic Prioritization or Killing the Liberal Arts,” Dutt-Ballerstadt described academic prioritization as “increasingly being employed…by administrators at liberal arts colleges and universities…to explain or justify decisions to cut certain programs.” It is the concept of administrators reevaluating which programs are of good value to a university in favor of generating more revenue.

Seeing how much the cost of higher education has gone up in recent years—according to the Education Data Initiative, the average cost of a four-year college degree has gone from $5,144 in 1963 to $101,584 in 2020—it only makes sense that students are being cautious. Institutions need to be receptive and considerate of this.

During a Strategic Marketing class this year, the School of Business Dean Benson Whitney said that in order to ethically steward money that students are entrusting to the school, the University needs to honor its commitment to help them get employed upon graduating.

Unfortunately, humanities often get left out of consideration when thinking about what counts as an “employable skill.” Maloney warns that many administrators hired to make these decisions are not the products of a liberal arts education, so it is hard for them to see the value compared to someone who is.

Sister Antonia McHugh, dean at St. Kate’s from 1914 to 1929 and president from 1929 to 1937, required all Katies to major in both a humanity and a technical trade. Though this is no longer a requirement at St. Kate’s, Dutt-Ballerstadt is seeing the danger of institutions that do not recognize the critical importance of humanities across– and in collaboration with– all fields, including business and the health sciences.

If we, as a liberal arts university, cease to educate on how to conduct certain disciplines, what message are we sending when it comes to respecting the need for those skills in daily life? What happens to the thoughtfulness for diplomacy, collaboration, fairness, empathy and equity?

When I asked Maloney about the danger of placing less emphasis and value on the study of humanities, she responded that, “in every serious, horrifying dictatorship of modern times, the fascists get rid of the artists and philosophers first. The humanities are where we learn to be human beings. We live in an era of incredible depersonalization and detachment. It’s cultural suicide to minimize the value of humanity and how to treat people.”

Both Maloney and Dutt-Ballerstadt agree that this fight did not start with St. Kate’s or Linfield. This dilemma has been building for decades, with Covid-19 only accelerating the decline in college enrollment. Job layoffs and inflation ate away at people’s savings and others decided virtual classes and isolated environments weren’t worth it at such a heavy price tag.

Today, many schools act like a business rather than a community of learning, and they must prove that their brand is worth something to prospective students and donors. Dutt-Ballerstadt says, “Liberal arts institutions are moving away from their mission- driven logic to market- driven and revenue-generating strategies . . . Such a business model is antithetical to a liberal arts education and disproportionately impacts the humanities and the social sciences.”

St. Kate’s is known for turning out exceptionally qualified nurses, physical and occupational therapists and exercise science specialists. Maloney says this is true because, “St. Kate’s healthcare professionals know how to think.” This is due to them receiving their training as part of a liberal arts education.

Healthcare workers are important, as the pandemic has only further demonstrated, but they need a good support network to succeed. The humanities students are the ones who will advocate for better wages and union benefits, run the campaigns promoting public health practices, legislate better working conditions, prevent workplace harassment and counsel the nurses going through the trauma that can come with a rise in gun violence, suicide, police brutality and reckless and unecessary Covid-death. Healthcare professionals are busy doing important work and need a network of support to make their lives more sustainable and that is where the need for variety in education comes in. We all work together.

If we do not maintain the integrity of our other worthy programs, we are devaluing the degrees that our alumnae hold and the institution itself in the eyes of incoming students. What will employers think of the skills a St. Kate’s graduate has learned in a field the University no longer deems necessary? What will donors think when they struggle to see the variety of ways Katies are equipped to lead and influence? By limiting our majors and courses, we limit the fields our students can lead and influence in.

St. Kate’s cannot standardize the opportunities students have to explore their options for future careers before higher education. It cannot be ignored how common it is to switch majors at least once. Many students are not exposed to the variety of fields they can pursue until they get to college. If they don’t know what they might click with, how can they decide what major to commit to?

“People value and prioritize what they know about,” Maloney says. If a student has no frame of reference for how sociology or economics works, why would they blindly invest money and commit to studying it for four years? Every class a student takes teaches them something of value, whether it be that they need to pay more attention to particular issues, a new skill, or that they don’t enjoy a particular kind of work.

The portfolio for a college needs to be well-maintained and wide, especially when so many students are only looking at schools that have reputable programs for what they are interested in. If St. Kate’s wants to keep students of all avenues in its community, the University needs to have alternative programs that are worth sticking around for even if students don’t end up wanting to pursue nursing. By hyper-specializing, a school does not prepare its graduates to appreciate perspectives from other disciplines with valuable insights.

St. Kate’s often only advertises the nursing program amongst all of the majors. Nurses produced by our renowned nursing program enjoy a great reputation and employability rate because their skills and “ability to think” makes them stand out.

However, St. Kate’s has some really impressive alumnae in other fields. U.S. Representative for Minnesota Betty McCollum, Minnesota State Senators Mary Kunesh and Erin Murphy, late American spy and founding member of the Central Intelligence Agency Elizabeth Sudmeier and former CEO of Twin Cities Habitat for Humanity Pamela Wheelock, as well as several federal, county and state court judges are all alumnae of St. Catherine University who studied fields like English literature, history, and political science.

There is so much St. Kate’s has to offer students across a variety of disciplines but those programs won’t receive interest from prospective students if the University does not honor and tell the stories of each of these departments equally. The answer is not to cut down on the humanities, but to get students to understand the value they hold in conjunction with fields like the health sciences.